Inside the world of Medical Motion Design

The human body is a fascinating place, but does it also contain a path for motion designers? No, we're not saying you should quit on your dreams to become a doctor (sorry, dad). Today, we're taking a look at the incredible field of Medical Illustration with an amazingly talented director, Emily Holden.

Emily is a Director at Campbell Medical Illustration in Edinburgh, Scotland. She comes from a fine art background, but found herself fascinated by biology and anatomy. Her curiosity and artistic skill led to a career helping clients visualize medical topics for various uses. Her work is pretty dang good too!

Campbell Medical Illustration, aims to make the body beautiful...while maintaining the incredible standards needed to support the medical community. Each client has a different need, and that leads to unique challenges. Patient-focused customers want the human body portrayed in a "friendly" way, so that lay folk won't be intimidated by what they see on the screen.

On the other hand, medical professionals need to see an accurate representation of human anatomy so they can understand the information being portrayed. If the tissue or cell structures are inaccurate, it takes the viewer completely out of the video. This is different from the normal client-artist relationship where a personal style helps you stand out. For CMI, accuracy is king.

This is a fascinating field that we know might be new to you, so scrub in. We're doing a differential diagnosis with Emily Holden!

The Motion of Medicine - Emily Holden

Show Notes

Artists

Studios

Pieces

LinkedIn Learning- Maya: Fundamentals of Medical Animations

Resources

Transcript

Joey Korenman:

Emily, it is awesome to have you on the School of Motion podcast. I think you're definitely the first medical artist that we've had and this is a field I don't really know much about, so I'm really excited to talk to you and I just want to say thank you so much for doing this.

Emily Holden:

Oh, thank you very much for having me. It's great. I'm a big fan of the podcast, so it's very exciting to be here.

Joey Korenman:

Oh, well, awesome. Well, thank you for saying that. So I wanted to start ... We're going to link to your work and to Campbell Medical Illustration's website online so all of the listeners can check out the beautiful work that you're doing. But I wanted to first get a sense of your background as an artist, because I did my Google stalking of you and I looked on LinkedIn and all the things I normally do, and it seems like, from the outside, you started as going down the traditional route of being just an artist and then you took this turn into this really niche thing. So, can you talk about the origin story? How did you end up deciding I want to be a professional artist, I should go to school for that?

Emily Holden:

Yeah. So I kind of discovered my passion for art in high school, where, I guess, everyone kind of realizes that's maybe what they want to do. I was really into portraiture and figurative work to begin with. As most people know, that subject matter can be pretty tricky when you're not very experienced in it, so I've got some really great, bad celebrity portraits hanging around in repairs garage and stuff somewhere that will just hopefully never re-emerge.

Joey Korenman:

Now, wait, can I ask you really quickly, because I feel like this is going to tie in?

Emily Holden:

Cool.

Joey Korenman:

So why were your portraits bad? Why do you say they're bad?

Emily Holden:

Oh, no, they were just what you do when you're trying out portraits for the first time. At the time, I thought they were pretty awesome, but I was 14, 15.

Joey Korenman:

Oh, sure. Well, because-

Emily Holden:

And so looking back, like, yeah.

Joey Korenman:

I'm jumping in way early, but I'm so fascinated-

Emily Holden:

Yeah, no problem.

Joey Korenman:

By this. If you're doing medical illustration, which, by the way, illustration doesn't just mean drawing. I mean, there's 3D. I mean, there's all kind of different techniques. But I would imagine realism and anatomical accuracy being really important, and so if you're doing figure drawing and you're drawing portraits of people, it seems like you really have to get that right before you can then add a little bit of subjectivity to it and stuff. So, I'm wondering if that's what you were talking about. Were you still not good at that stuff yet?

Emily Holden:

Yeah. I think what really started me off in art was portraiture and figurative work. I was always interested in people and trying to capture people, people's faces and expressions and that, and really trying to work on photorealism and stuff. And it was always a goal of mine to be able to make stuff look like those really photorealistic, beautiful portraits or the beautiful classic kind of portraits of Rembrandt or Caravaggio or all these big classic painters and stuff. But I think-

Joey Korenman:

And were you painting at the time or was it illustration?

Emily Holden:

Yeah. Well, yeah. I started doing painting, I think, in high school with the coursework. It was one of those things that all the teachers were like, "Don't do faces. Everyone, draw a flower. Don't even go there. Don't try and do faces, you probably won't get a good grade." But it was one of those things that I just absolutely loved, so I just kept going for it. And I was very lucky that my school was very supportive of it, they're like, "Actually, you're not doing too bad a job, so keep going."

Joey Korenman:

Oh, that's encouraging.

Emily Holden:

Yeah. So I kept progressing with my art and stuff through school. I used art a lot as an escape mechanism, I think, when I was younger. I went through a pretty rough time as a teen and it was always a good way of expressing thoughts or feelings or things like that, so I spent a lot of time drawing. So I think a good thing to come out of all of that is that I spent hours and hours and hours escaping into drawing and trying to perfect it and trying to get my skills up to a level that I was happy with, because it was always my dream to kind of ... Well, at the time, I wanted to go on to become a successful painter and live out that artist life of being in a studio covered head to toe in paint and staring wistfully at a canvas-

Joey Korenman:

Sure.

Emily Holden:

And not being outside in the real world, things like that. But then I soon realized that I was actually quite painfully shy about my work and, I guess, that kind of artist mindset that you actually have to go out and sell your work.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah.

Emily Holden:

Doesn't just happen that you get to paint your whole life and then people just give you money somehow, it's like no, you need to be able to also have confidence in it, sell your work, find that market and that. I never really knew exactly what I wanted to do, I think. I wanted to be a painter, but I think the painter and artist life maybe wasn't always right for me somehow.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah. I mean, if someone said right now, "I want to be a professional artist," I mean, there's a lot of clear paths to do that for different disciplines and I imagine for medical illustration, there's probably a pretty clear path if you can go to school and afford to do that. But to be a fine artist and to do gallery showings and all that ... I mean, I don't know very much about that world. One of our instructors actually, Mike Frederick, he's an amazing painter. He can do photorealism and all that stuff, and he's done showings and stuff, so I've learned a little bit about that from him. But it sounds very cutthroat and political.

Emily Holden:

Yeah. I think I-

Joey Korenman:

It's who you know.

Emily Holden:

Definitely didn't have the skin for it.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah.

Emily Holden:

Because, straight out of high school, I went to Edinburgh College of Art to study painting. And I'd initially wanted, actually, go and become an art therapist as my backup if I don't become a full-time artist, I want to go and do a post-graduate in art therapy because I love the idea of art materials and the creative process, helping others to explore their motions and work through psychological issues and stuff. But it was one of those dreams that I also realized it wasn't really suited to me. I was reading through the syllabus and it mentioned oh, you need to go and do a research study and interview all these people and that, and I was like, "Oh, no, people."

Joey Korenman:

Oh, God.

Emily Holden:

Yeah, I was like, "Oh." So I was like okay, I'll draw a line over that as well. So I just continued with my studies, trying to work out exactly where I fit in, I guess, the art world, I guess. Edinburgh College of Art didn't really focus on traditional art skills, so it wasn't like everybody, sit down and let's learn how to do an oil painting, it was very much encouraging people to be experimental and find their place in the contemporary art scene and it felt very competitive. And so I was jumping around loads of different ideas for a while, but then I finally found, I guess, my calling in anatomy drawing, I guess.

Joey Korenman:

Well, how did that happen? So-

Emily Holden:

Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah. And just so everyone listening knows, so you're in Edinburgh.

Emily Holden:

Yes.

Joey Korenman:

By the way, are you from Edinburgh and are you from-

Emily Holden:

Yeah, I am.

Joey Korenman:

A different part?

Emily Holden:

No, this is ... Yeah. I've not really left. I've lived in another city in Scotland for a year for studying my master's degree and then that was it, back to Edinburgh. I just really like it here.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah. Well, I mean, I've never been. I was talking to Nuria Boj, who's also living in Edinburgh now, and I was telling her how jealous I am because I really want to go to Scotland really badly. And now I know two people there, so that's awesome.

Emily Holden:

Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah, that's great.

Emily Holden:

Come any time.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah. So you're at the Edinburgh College of Art and then it seems like you immediately went into a master's degree.

Emily Holden:

Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

And it's a master's degree I've never heard of up until I saw it on your LinkedIn, which is medical art. So, I'd love to know how did you discover that that's what you want to do?

Emily Holden:

Yes. Yeah, I'd never heard of it either. So towards the end of my undergraduate degree, it was fourth year and then the ... Well, my work had started going into anatomy just out of my own curiosity and stuff, and I was a bit of a collector of old stuff, like old books and cameras. And one day, I found this amazing old anatomy textbook in a secondhand store and it was full of these weird, disembodied structures with the Latin names underneath them and my mind was pretty blown by them, like, what is this? It was like a book full of illustrations of parts of the body I'd never seen before, these inner intricate anatomical structures and all these things were inside me. I was like, I have one of those, but what is it? It just burst this complete fascination with the relationships that we have with our body, its anatomy and then that spiraled onto the history of anatomy and surgery, the commodification of the body throughout history, the disgust we feel for what lies beneath our skin.

Joey Korenman:

Right.

Emily Holden:

Just this huge web of stuff that I was looking at and going, "Whoa." So that's kind of how my end of ... My undergraduate ended with all work all inspired by this kind of stuff. And I did a lot of dissection drawings in the anatomy and veterinary departments of the University of Edinburgh. I asked for permission to go in and draw some of the specimens that they had there and, thankfully, they said yes because it was a really invaluable experience and it ... Just found something that I was really passionate and really fascinated about. And I think a lot of people, when I tell them that, they're a bit like, "Okay. Ew. Why?" But I don't know-

Joey Korenman:

It's a little ghoulish, but ...

Emily Holden:

Yeah. It's just this kind of precious thing about life and it's all these little things that actually go into making people or animals and things, and it's like you don't get to see them, but they make the person who they are or they make the animal what it is. It's all these ... I don't know. There's something about them that I find just extremely interesting, but yeah.

Joey Korenman:

I was in Portland a little over a year ago and I was there with Sarah Beth Morgan, who teaches our illustration class, and she took my team and I to a taxidermy store. It's a long story why we were there. And I'd never been to one. It was simultaneously some of the most beautiful things I'd ever seen, but with this layer of memento mori just laid right on top.

Emily Holden:

Yeah. Definitely.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah. And it's a really neat feeling. And that was kind of the whole point of going there was ... That feeling that you get when you see a beautifully dissected deceased thing, that feeling is impossible to get any other way.

Emily Holden:

Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

Nothing else makes you feel that way, so you have to go see it to feel whatever that is. That's really fascinating. And so it sounds like you were sort of attracted to that. And then what did the master's program teach you? Was it more of an art program or more of a ... Almost like a premed program?

Emily Holden:

Yeah. So the way that it's broken up, in the first semester, you're doing medical illustration assignments and life drawings, but you're also getting taught anatomy. So there's quite intense teaching in head and neck anatomy and general anatomy, and that's done in the dissection labs in the University of Dundee as well. So you're kind of juggling both, you're trying to learn all these things super fast in very much a scientific way as if you were an anatomy student, but then you're also trying to, I guess, start developing those medical art skills, like being able to look at a dissection, work out what's significant, how you lay out your information, and then also start using digital illustration tools, like Photoshop, like drawing on Photoshop and Illustrator and things like that. Yeah, it was quite a lot. Yeah, very busy year.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah. And were you dissecting things yourself or were they already dissected and then you're ...

Emily Holden:

Yeah. So most of them would be partially dissected because we would go in after the anatomy students had been in and had their teachings and stuff as well. But we also did get the opportunity to do a little bit of dissection, if we wanted, as well. It's a bit of a gruesome detail to go into, but in Dundee, their dissection lab, they've got a different type of embalming technique called Thiel embalming, and that maintains the flexibility of the specimens. So, normally, you would have a plastinated specimen, could be a human hand or something and it's gone through this process called plastination. It's the same process that's used with ... You know the Body Worlds Exhibitions?

Joey Korenman:

Yes, I've heard of it. Yeah.

Emily Holden:

Yeah. So that's kind of what you traditionally see and it's all very stiff and you can't move it around. But the Dundee program, in their anatomy department, they're all Theil embalmed, so very flexible, everything's still got quite a lot of color.

Joey Korenman:

Wow.

Emily Holden:

It feels a lot more real, I guess.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah. And were you-

Emily Holden:

Very ... Sorry.

Joey Korenman:

You were working with human cadavers and things like that?

Emily Holden:

Yeah. Yeah. So that's what all of our anatomy training ... We had to do anatomy spot tests, so here's a heart or here's a spine, can you identify what's on this little flag? What's this called, or-

Joey Korenman:

Yeah.

Emily Holden:

What's this called? So it's-

Joey Korenman:

Oh, wow.

Emily Holden:

Yeah, things like that.

Joey Korenman:

This is fascinating, Emily. It's funny because my father was a surgeon for, like, 40 years, so he-

Emily Holden:

Oh, cool.

Joey Korenman:

Made his living cutting bodies open and fixing them. I've never really been good around that stuff, but I remember doing dissections in high school and what blew my mind ... When you see an anatomy chart, the arteries are red, the veins are blue, the muscles are purple. Everything's so easy. When you actually open up an animal or ... I've never actually seen a dissected person, but it all kind of just blends together.

Emily Holden:

Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

How hard was it for you to learn to identify things? Because it's not like it looks on the poster.

Emily Holden:

No, it's definitely not. Yeah. That beautifully illustrates exactly why you need medical illustration, I guess. I've had people in the past say things like, "Oh, what's the point in medical illustration? You can just take a photograph." And I'm like, "Well, no." Nobody wants to see that, for one.

Joey Korenman:

Right.

Emily Holden:

And then also, to label a photograph would be an absolute nightmare to work out what's going on and you need to be able to take away the parts that aren't necessary, take away the parts that are acting as any barrier to the person learning from that image, I guess. So-

Joey Korenman:

Yeah.

Emily Holden:

Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah. I mean, there's so many layers to all of it. So you just brought something up that I wanted to touch on, which is, obviously, I think one of the roles of medical art is to simplify because even if you open up ... I remember we had to dissect, I think, a cat in high school and it's like man, cats are complicated. There's so many pieces and parts. And you open it up and it's all just this dull pink or brown, you can't tell what anything is. So the art lets you just simplify things and identify things. But also, you brought up that no-one wants to look at a photo of-

Emily Holden:

Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

Of tissue. There's something visceral and kind of gross to most people about that. And so I was wondering, obviously, when you're creating an illustration, it has to be accurate, but it can't be too accurate because that would just be gross, right?

Emily Holden:

Yeah, absolutely.

Joey Korenman:

You can't have it look slimy and bloody and all of those things. So, how do you manage that, the balance of it has to be accurate, but it also has to be beautiful and not in this morbid, gross way?

Emily Holden:

Yeah. I think the thing with medical illustration and animation, I guess, it needs to look interesting and have an impact to capture the viewer's attention, but not in a gory way. So it's important that whatever you're creating, you're not actually putting people off looking at it. And I think if you were to portray it in that visceral, gooey, bloody way, then people will just be like, "Ugh. Ugh, what's that?"

Joey Korenman:

Right. Right.

Emily Holden:

"I don't want to look at that." It's the good part of trying to find that balance of what is still portraying, realistically, what is there, but visualizing it in a way that's really accessible because a lot of the time, these illustrations or animations are used for education. I think that's the main thing about it, it's part of storytelling and you're trying to tell the science story and anything that detracts from that is not needed. So in a photograph, you'll have all these other structures or you'll have a little bit of blood or a little bit of something going on, and then what you really want is you just want to see what does that muscle look like? What is that vein beside it? What is that vein called? Where does it go? Where does it come from? It's being able to distill all that information and lay it out in a way that makes sense and a way that just makes people want to look.

Emily Holden:

I think a lot of what I do comes down to what the client's actually looking for as well. Their intention may be that they actually want something that's very bright or contemporary or bold, or they might actually want something that's more traditional, textbook-style. Most of the time, they're wanting something that's bright and edgy and bold, and this is for a number of reasons. They often have, maybe, new research that they want to present in scientific publications or a conference and they want to really stand out from their peers and be like, "Well, yeah, your research is interesting, but look at this one."

Joey Korenman:

Right. Right.

Emily Holden:

And also, they may be creating patient information videos and resources, and that information needs to be really accessible and appealing to the target audience.

Joey Korenman:

To me, that makes so much sense because I would imagine if you're making something that's going to go in front of a patient who's going to have surgery or a device implanted or something, you want it to look as harmless as possible.

Emily Holden:

Exactly.

Joey Korenman:

If this is for doctors, maybe, to sell them something, maybe ... Do you have to make it more realistic if it's a medical professional who actually sees this stuff for real, or is it always about making it appealing?

Emily Holden:

Yeah, I think it depends on exactly how ... If it's for someone who's maybe an expert in the field, then they kind of know what they're doing. So maybe if it is looking more appealing, then it's just going to gage their interest a little bit more because they already know, from experience, what it maybe looks like in the real world. For, maybe, teaching students and stuff, having an extra element of realism would probably be beneficial. And then, as you're saying, with patient informations, sometimes some really nice vector art and character design and some nice motion graphics is exactly what's needed for it.

Emily Holden:

And, like you said, if you were describing a surgical procedure, the patient definitely does not want to know exactly what this is going to look like because it's just scary and it just completely puts them off maybe having the procedure or it raises their anxiety or the blood pressure or something. It'll get them in not the best zone. They need to go into surgery being completely informed about what's going to be happening so that they give their consent, they're like I know what's happening, I'm okay with what's happening. But if they were to get shown a video of the surgery, they'd probably ... Not probably, potentially freak out a little bit and be like, "No, not happening."

Joey Korenman:

Right.

Emily Holden:

So ... But that's how-

Joey Korenman:

If you show a video of the surgery, it would be terrifying.

Emily Holden:

Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

But if you show them the cute explainer video-

Emily Holden:

Yeah. Yeah, totally.

Joey Korenman:

It's better.

Emily Holden:

With a nice little friendly character and you're like, "Oh, I trust this little guy."

Joey Korenman:

Yeah. Some ukulele music.

Emily Holden:

"This guy will help me get better." Yeah, absolutely.

Joey Korenman:

Exactly. So I want to learn a little bit more about who are the clients for this kind of thing? I mean, I can imagine pharmaceutical companies and you're talking about maybe hospital groups or something, where this is a video for their patients. But who hires Campbell Medical Illustration primarily? What are the types of companies?

Emily Holden:

Yeah. So we have a mixture of companies that hire us for work. We work with research institutes and independent doctors and surgeons, there's also medical device startups all the way through to very much more established medical device and pharmaceutical companies. So they might have a new medical device for implanting something in the body, they need marketing material to promote this, but also instructional material to teach people how to use it as well. There are also companies that focus on training tools for nurses and doctors. We do a lot of animation and images for them as well. And also, things like ad agencies to do content production if they have a large medical client and they need to work with the company who have that medical expertise as well. And more recently, we're working on more commercial brand names, they'll usually reach out and want anatomical illustrations that are accurate, but also highly branded to their content as well. So yeah, that's kind of-

Joey Korenman:

Yeah. That's really cool. So-

Emily Holden:

Everything.

Joey Korenman:

So, I mean, how big is this niche? Because you're in the world of design and animation, which is fairly big, but it's like this really narrow focus on a certain expertise. But are there a lot of clients or is it a small pond?

Emily Holden:

I think it's a field that is constantly growing and it's also something that, I think, there's always going to be a need for it. There's always going to be new procedures, there's always going to be new drugs coming out, there's always going to be new ... It's just a constantly evolving field. So, service are pretty in demand, and more and more medical companies, doctors and surgeons are wanting to connect with their patient audience and they're finding that investing in high quality and good looking graphics is helping to bridge this gap. Medical art field is relatively young, but it is growing substantially.

Joey Korenman:

I love it. I love hearing that. I mean, it makes so much sense. I used to live in Boston and the biotech startup scene there is crazy. I mean, there's just tons of new drugs and AstraZeneca, I think, had a huge office there. I mean, there's a lot of this work out there. So how do these clients find you? Because in just normal, everyday motion design, there's a million ways to get work and you can reach out to people or they can just find you through Instagram. But I would imagine that these kinds of clients probably aren't on Instagram, looking, following medical illustrators, so how do you get this kind of work?

Emily Holden:

I think we're just very lucky that our website is just doing its job quite well for us, I guess.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah.

Emily Holden:

I think it's just a case of typing in medical illustration or medical animation, if you add-

Joey Korenman:

The company name and the URL is 100% perfect for-

Emily Holden:

Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

For being discoverable, so that's really good.

Emily Holden:

Luckily, people find us. It is normally just straight through the website, so yeah.

Joey Korenman:

That's awesome. That's really awesome. And so, and you can talk about this as much as you're comfortable, but-

Emily Holden:

Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

This kind of work, when most of our students, I guess, get into motion design, I bet a bunch of them don't even really know that this is a thing you can do and, hopefully, this podcast will open up their minds. "Oh, wow, this is really cool. This is something I could be doing and be interested in." As a business, you can make a pretty great career out of doing explainer videos and, I mean, just more technical videos and things like that. And different clients have different budget ranges. So for these types of videos, if you're working for a pharmaceutical company or a biomedical startup or a hospital group, are these generally healthy budgets and you can make a good living, or do you have the same issues everyone has, where it's like well, we want a fully photo reel rendering of the lungs, but we only have ...

Emily Holden:

Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

We only got this much.

Emily Holden:

I think it generally just depends on who it is. I think it's the same ... I think it's probably quite consistent. There is a lot of money in big pharma companies and stuff like that, but I think it's ... I guess it's just the same with everyone. The big projects will come around maybe now and again, but it's not ... I wouldn't say come and jump into medical art, there's so much money here and all the big bucks are here. Yeah. I think it's probably quite the same across board, I think.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah. That's good to know. All right, so I want to talk about the technical side of all of this. So I think a lot of people listening to this are probably looking at your site and they're saying, "Wow, it's beautiful stuff." And I'm looking at those veins and with some plaque buildup in them and some blood cells, and I ... In Cinema 4D, I could totally make that, I know how to do that, but I do not have a master's degree in medical art, I can't tell a vein from an artery, I don't know all the muscles of the hand. How much medical background do you need to be able to do this?

Emily Holden:

I think it probably depends on exactly where you're going and who you're working for. There are some companies that hire more generalist medical animators and then they'll have a separate team of staff that are specifically doing the science content and things like that, and making sure that everything is completely scientifically accurate before the 3D animator or 3D modeler has anything to do with it. I'd say this is one of the main things that made me want to go on to do my master's degree is that when I was doing all my illustrations and stuff in the dissection labs and stuff, I got the opportunity to do my first medical illustration job and I was like, "Oh, this is great. Cool. Amazing." And it went fine in the end. But I think I knew that while I was doing it, I didn't know what I was drawing. And it was that thing like ah, no. And it gave me a kind of anxiety with talking to the client as well because he was like ... It was all about gastric band surgeries. He was like, "Oh, can you make sure that this bit comes out the top of the diaphragm?" and blah, blah, blah. And at the time, I was like, "What?"

Joey Korenman:

What?

Emily Holden:

"What?" And then I was scared to tell him that I didn't know what he was talking about, so it was just this battle. But I think at least having a basic knowledge of anatomy or at least knowing how to do good research, just even knowing how to start learning about anatomy is probably needed.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah.

Emily Holden:

Because sometimes you'll get a client who'll come and be like, "Right, so I want to do this illustration of the nerves of the head and neck. And this is the list of the cranial nerves that we need to show and we want to show all of the muscles and all the cell tissue, it needs to show the correct path of all the nerves." And then if that was me coming at it from a complete, I guess ... Without any anatomy knowledge, I would probably just curl up in a ball and be like, "I can't do it. I don't know what you're talking about." Because they'll probably use all of the medical jargon as well. Whereas, because I've got the solid basis in my training, I can be like okay, I know what you're saying. And if I'm not exactly sure where some things should go, then I know how to research it so that I can actually produce an accurate piece of work for the client. So-

Joey Korenman:

Yeah. That makes sense. That makes perfect sense. I mean, you have to have at least enough familiarity with it to know even what is being talked about. Yeah. Okay, so focusing on that ... That was a good example you just gave because-

Emily Holden:

Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

No, because if someone came to me and said that, I would not have a clue where to begin. The medical side of it is one piece, but then the other part is, then, you have to somehow produce this thing, right? And the human body is not a simple thing, it's very-

Emily Holden:

Definitely not.

Joey Korenman:

Very detailed, very complicated. So for something like that, are there models you can purchase? Are there pre-existing assets that have everything and you can turn layers on and off? Or do you have to basically go into ZBrush and model this and create it bespoke every time?

Emily Holden:

There are resources out there. There are some good quality anatomy models out there, some are rigged up and everything, that people can purchase a license for. They're pretty pricey, but I guess it's an investment for once you have it, then you can do what you want with it. I guess the only thing is having that little bit of anatomy knowledge in the back of your head as well, so you can't trust it-

Joey Korenman:

Right.

Emily Holden:

In everything that you get is going to always be 100% accurate.

Joey Korenman:

Right.

Emily Holden:

So it's kind of being able to just double-check, right, I've purchased this model, I now need to actually go and check that everything is in the right place because ... Yeah. It just needs to be accurate.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah.

Emily Holden:

But no, there is. So with every project, a lot of studios will have their base human anatomy model and then they can work with that, they can use assets from that to either take into ZBrush to model them a bit more or completely animate them and rig them up and do cool stuff in Maya and stuff. Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah. So I want to talk about the different roles in this field. So you mentioned that some places will separate out the artist from the expert and they'll have, I'm assuming, a medical consultant or maybe an actual MD doctor or something like that to consult. So it sounds like that's not how it works at Campbell.

Emily Holden:

No.

Joey Korenman:

You're all sort of the expert and the artist?

Emily Holden:

Yeah. So we've all got our master's degrees, so we all have that base anatomy knowledge as well. So we're responsible for doing all of our own research, so we would expect one of our members of staff to be able to do their own research, put together all of their initial sketches and everything, and then provide us with a folder full of references of exactly where they got these specific positionings from or things like that, because that's another thing that we often provide to our clients because everything needs to be accurate. What we do is we package up all of our reference materials and we will give them to the client for their review so that they know that we have placed things for a reason and we're not just winging it and being like, "Yeah"-

Joey Korenman:

Just freelancing it. Yeah.

Emily Holden:

"That's right." Yeah. Because I know we've done-

Joey Korenman:

Yeah, I'm pretty sure.

Emily Holden:

Extensive research and based on this, this is why it looks the way it does.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah. So that skillset you just described is not a typical motion designer skillset.

Emily Holden:

No.

Joey Korenman:

So-

Emily Holden:

Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

And I don't know how often you need to find a freelancer to help on a project, but, I mean, is it hard to find artists that have all those combinations of talent?

Emily Holden:

I think the field is a nice size, it's not huge and extremely competitive. It's a very close community as well, kind of medical art community, so we will know a good handful of people that we can reach out to that we know have maybe graduated from one of the American programs or one of the North American programs or something like that. So, we can reach out to them and be like ... We know that they know enough so that they can quickly jump on something, I guess.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah.

Emily Holden:

I wouldn't say that we would never hire a generalist because at the stage that it would actually get to the point that we would need someone to make the 3D part beautiful or whatever, we would probably handle all the research and the storyboarding and the basic modeling and stuff. So, there would be space in the pipeline for a generalist to come in and either do final finessing or final animation based on, maybe, our heavy, heavy art direction.

Joey Korenman:

Right. Right. So that brings up another question. So looking at some of your work, I mean, this is some pretty gnarly technical 3D, some of these things, right? This isn't nice, shiny orbs floating around with some nice lighting, I mean, this is some pretty gnarly rigging and stuff like that. So, along those lines, I mean, are you and the team also generalists in that way, where you've got the medical background, you have this art background so you know how to compose frames and choose colors that work together? And then, on top of that, are you modeling things and rigging them and lighting them and setting up the render passes and the camera moves and all of that?

Emily Holden:

Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

Or is there-

Emily Holden:

Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

Some division of labor there?

Emily Holden:

At the moment, we're working that we'll pretty much ... One person of the team will go at it-

Joey Korenman:

That's amazing.

Emily Holden:

The dream would be to have a nice sized team that we could maybe delegate tasks, but, at the moment, we assign a project to one of the members of staff and then we'll pass it around and jump it around people, if you think someone might be able to approach something slightly better. But we don't have a team set up where one person's doing the modeling, one person's doing the rigging, one person's doing the lighting. That's the kind of dream, big 3D studio set up, I guess.

Joey Korenman:

Great.

Emily Holden:

But no, we would like everyone to maybe eventually have all these skills.

Joey Korenman:

That's amazing. I mean, honestly, that's a testament, I think, to just how good artists have gotten and how the tools have become so accessible. I mean, 20 years ago, there was no chance one person would be able to do all of this.

Emily Holden:

Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

There's just no way. So I haven't really done medical animation. Although, actually, I did work on a commercial for a Novartis drug, I think, at one point.

Emily Holden:

Cool.

Joey Korenman:

And so I had to animate blood cells. Yours are much prettier than mine. But yeah, I did work once for an architectural firm doing some motion graphics for them and they had a huge team, and everybody specialized. It was really pretty cool to watch. And I don't think any one person could've done all the things because it was so technical, but now, I don't know, maybe that's just the way it is now.

Emily Holden:

Yeah. I think myself and Annie, the other director of the company, we just have this great passion for learning, so I think we're just like ... We're like, "I want to be able to do that," so we'll just get in that head space and just teach ourselves that.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah.

Emily Holden:

And that's what we hope that all of our employees would do as well, just have that motivation, like I can't do that. Instead of being like, "Oh, I can't do that," you'd find someone else who's like, "I can't do that, but give me a couple of days and I will watch every tutorial under the sun and I'll make sure that I can work this out." I guess that's just the kind of team spirit that we have. If we need to learn Houdini in four days, we will try and learn as much of Houdini in four days as we can.

Joey Korenman:

Amazing. I love it.

Emily Holden:

Yeah. Like, "Oh, this tool looks like it can do exactly what we want." "But we don't know how to use that." "It's fine, we'll work it out."

Joey Korenman:

Listen, YouTube is a thing, we'll get on there-

Emily Holden:

Yeah, it's the best thing in the world.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah. I mean, I've talked to a lot of artists and some really, really, really successful ones and, I mean, there's ... I always try to look for the commonalities and that mindset is definitely way up at the top. I have three kids and we have this rule in my house that if I ask them to do something or they want to do some gymnastics move and they say, "I can't do it," they have to do push-ups because-

Emily Holden:

Nice.

Joey Korenman:

What they're supposed to say is I can't do it yet.

Emily Holden:

There we go. I like that. That sounds great.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah.

Emily Holden:

Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

It's amazing to see the level of work that a small team, like Campbell Medical Illustration, is able to pull off just through sheer willpower. It's amazing.

Emily Holden:

Yeah. Yeah. Thank you. Yeah. It's definitely a labor of love. I think that's the thing, I think if you're passionate about what you are creating, then if it's hard and you need to put in the long hours and it's always worth it in the end. You're always just adding another tool to your belt. I think that's just the best mindset to get into. I think, with anyone, if you're even starting out just drawing, you'll do your ... Like I was saying before, you'll do your first portrait, it'll be horrible, you'll hide it forever, but eventually, you'll have this big pile of drawings and the one at the top that you'd just finished is going to be the best one you've ever done. So, I think that's the best thing about working in the creative field is that the work that you do now could, potentially, be the best work you've ever done, so it's worth just pushing it and getting motivated and just-

Joey Korenman:

Love it.

Emily Holden:

Doing the work. Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

Love it. So let's talk more about the technical stuff, let's get into the weeds here. What's your software stack at the company?

Emily Holden:

Yeah. So we use the same software as many of the other design agencies, like Photoshop, Illustrator, and our main animation tools are After Effects and we use Autodesk Maya. That's just out of preference, there's so many different 3D softwares out there and that just-

Joey Korenman:

Yeah.

Emily Holden:

It just so happens that that's what I was taught and that's what Annie was also taught, and so we're just sticking with that.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah. I mean, I haven't used Maya in a really long time, but I watched ... I can't remember if it was you or Annie, but one of you has a YouTube channel with tutorials.

Emily Holden:

Yeah, that's me. Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

Is that you? Okay, yeah.

Emily Holden:

Yeah, that's me.

Joey Korenman:

We'll link to that.

Emily Holden:

Cool.

Joey Korenman:

We'll link to it. Because I watched one and you were doing things in Maya, I think you were animating villi or something.

Emily Holden:

Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

And it was really cool because I-

Emily Holden:

That was my first one.

Joey Korenman:

Oh, yeah. Great.

Emily Holden:

My first tutorial.

Joey Korenman:

You were good at it. So I was watching it and I would imagine most people listening to this, if you're doing 3D, you're using Cinema 4D because that's more prevalent in motion design. And I remember then ... Cinema 4D, I don't know how familiar you are with it, Emily, but there's this feature in it called the MoGraph tools.

Emily Holden:

Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

And in Maya, I know that that was one of the things that ... It either didn't have it or you had to have an add-on or it wasn't as good. And now, it seems like it has that tool and it's just called something else.

Emily Holden:

Yeah. Yeah. I can't remember, it was quite a long time ago now, but they added in MASH, is what their tools called, the motion graphics tool set.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah.

Emily Holden:

And I remember when that came out, I was like, "Oh, my gosh, finally."

Joey Korenman:

Yeah.

Emily Holden:

Because I remember just looking at all these people doing all these really cool things in Cinema 4D and just oh, you just press this button and suddenly, you've got 25 duplicates of the same thing. I'm like, "Ah, that'd be handy."

Joey Korenman:

Yeah, sure would.

Emily Holden:

And then finally, Maya did it as well. Well, that's when I started doing my tutorials on YouTube. I was like, "Oh, okay, this is exciting." I think I just had that bit of enthusiasm because I was excited about learning a new tool and I was like, might as well just film it and put it on my YouTube to try and teach other people how to do it because ... Because we are such a niche field, you can't just type in how do I animate the villi of the small intestine, because it's not going to come up with anything unless someone's actually made that. So I was like right, I'm going to try and fill in that gap. So if someone would like to be like, "Right, I want to do an animation on cell division," they'll just type it in YouTube and then I've made it for them, so they don't need to spend hours trying to work out how to do it themselves. So, that was the goal of doing that was to try and just help other people because I'd spent hours myself and I was like, I don't want other people to spend hours doing this as well, when I could just help them out.

Emily Holden:

But it was good because that led me to do ... I also did a LinkedIn Learning course called The Fundamentals of Medical Animation. So that's on LinkedIn Learning for people to go in and have a look. They can initially use the 30 day free trial if they're not wanting to commit to the full subscription to begin with and just check it out and-

Joey Korenman:

That's awesome.

Emily Holden:

Yeah, a lot-

Joey Korenman:

That's so cool.

Emily Holden:

Yeah, a lot of the stuff that I didn't really do on my YouTube has ended up in there, so-

Joey Korenman:

Yeah. I mean, from a technical standpoint, you're doing the same things that you would do on a commercial or an explainer video, it just looks different and there's a little bit of a higher bar in terms of accuracy. I want to ask you about what's the render pipeline that you're using over there? Are you using GPU renderers? Are you using Maya's native render or whatever that is? Are you compositing a lot? Are you doing depth of field in camera? Let's get geeky. How much of this is happening in 3D, how much is happening in 2D?

Emily Holden:

Yeah. If it's a 3D project, then most of it is happening in 3D. We were using Arnold Renderer, which is Maya's built-in renderer, for quite a long time, until, I think it was, maybe last month or something, I'd been geeking out about Redshift for ages and I was like, "Ugh"-

Joey Korenman:

Yeah.

Emily Holden:

I was like, "Can we just buy"-

Joey Korenman:

It's awesome.

Emily Holden:

"A couple of licenses, please?" And I just played on it for two minutes and I was like, "Oh, my God. Why have we waited so long?" Everything just looks really pretty. I don't know how, but it feels like it's easier to make things look good in Redshift.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah.

Emily Holden:

And it is a lot faster than Arnold, I found. I've not had the joy of trying to render out any sequence from Redshift yet, I've not had time to play on any personal projects or anything. But yeah, that's what we're using. I guess it's the same with many other animation companies, if you can composite, definitely composite. If it's not going to make much of a difference to do it in 3D as if you can just layer it up, then that'd be great. It really depends on the shot whether we'd render out a separate depth pass or anything, I think, because with ... Sometimes with medical animation, you'll see that there's a lot of really short sequences really close into that and then it goes off to another part really close to that. So, I think, sometimes when you're doing a full huge environmental scene that goes on for a longer time, it may be more useful, but I don't know. Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah. Well, I mean, actually, that just occurred to me because you're doing things that are microscopic and so I would imagine, a lot of times, you're making the choice of having a really shallow depth of field so it looks small, right?

Emily Holden:

Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

And so doing that in comp, it's just not going to look as good.

Emily Holden:

Yeah. It needs to be ... Yeah. If you do it in camera effects, it just always looks a lot more bang on.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah, exactly.

Emily Holden:

We're experimenting with the Redshift cameras and putting on the bokeh effects on ... Lens effects and stuff to get some chromatic aberration stuff that we would normally do in comp, but it was coming out really nice in the Redshift renderer itself. It's like oh, this is just lovely.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah. That's really cool. So one of the things that I've heard from people who work on car commercials is that a lot of ... I mean, way more than most people would think, car commercials, there's not a real car there, it's a CG car, you just can't tell anymore. But they have to have lots and lots of passes because the clients are so picky about the exact color and the exact amount of shininess and can you just make that tire a little bit darker? And so do you ever run into that with your clients, where they're like, "You know what? That blue is not exactly what that part is, or that pink"?

Emily Holden:

Luckily, we haven't had that, but yeah, it could happen.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah.

Emily Holden:

I think, a lot of the time, when the client's pretty much signed off on all the colors and everything by the time we get to that stage. Because, sometimes, it will be more on a cellular level of stuff as well, so it's not trying to match exactly to, say, a product or something. So, it's probably not as often that would come up for us that we would need to do a complete color change-

Joey Korenman:

Right.

Emily Holden:

Or we couldn't maybe adjust slightly using a bit of a hue change in After Effects.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah. And plus, I'm guessing most people don't actually know what color your liver is and stuff like that.

Emily Holden:

Yeah, there's parts that are just ... Especially when you go into the microscopic world, it's all very much ... I guess that's one of the nice, fun creative parts about that is that you can really play with color and color theories and stuff, and you can really get exciting with color palettes and stuff. It doesn't need to be as realistic as if you were rendering out muscles or something like that, it can be a bit more fun and colorful, which is ... It's always a lot of fun to do.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah. Ah, man, it sounds like such a fascinating field. So I have a couple more questions for you.

Emily Holden:

Yeah, no problem.

Joey Korenman:

And one of them is, I would imagine that with the COVID-19 pandemic, that there would be some impact on this field. And if I'm guessing, I would guess that it's been more work for companies like yours. But I wanted to ask you, what has the impact been on the business, having this pandemic?

Emily Holden:

I think, for us, we're pretty lucky in ... Well, as long as we have a computer, we can work anywhere, so that's great. We're all just working from home and working remotely. And all of our ongoing clients are shifting things around and some of them have started to create things to help with the COVID effort and stuff, so we're supporting them in creating some instructional content for that as well. I can't speak for everyone in the situation because it's hard to know, but I would say that there is a lot of need for COVID's resources at the moment and I think it probably has ... People have probably been looking more for medical artists and illustrators. I'm sure that you're pretty familiar with all these virus molecule renders that have been going round a lot, so there's a lot of information coming from them. And they're all based on real ... Well, a lot of the one, like the one from the National Institute of Healthcare, their one is created from the actual protein data.

Emily Holden:

So one of the tools that we use for doing molecular work is UCSF Chimera, it's a great tool and it helps us bring these protein structures from the protein data bank, which is all very scientific information, but then we can easily use this data and create very highly accurate models there. So you've probably seen a lot of these really highly detailed virus structures or things like that, that [inaudible 00:51:27] made up of tons and tons of little components. There'll normally be data extracted from there, and then the artist has worked on them or build them up.

Joey Korenman:

Wow. So it's sort of like a CAD model-

Emily Holden:

Pretty much. Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

Of the virus-

Emily Holden:

Pretty much, yeah. So you-

Joey Korenman:

Wow.

Emily Holden:

Go in, you kind of know what you're looking for or you know its exact ... The protein number that you're looking for, you go in and then there's sometimes a bit of assembly to do. You need to know what you're looking for in order to get it, but that's how a lot of models become very highly accurate is there are these amazing tools out there. Because there's a lot of overlap with scientific research and people want things to be visualized in a 3D way so that they can better understand it, but then medical artists can also use those tools in order to create other resources.

Emily Holden:

So another more specialized software we would use is imaging software, like 3D Slicer or InVesalius, and they help us use datasets from CT data or MRI scans. It's all done loads of different images on every plane of the body, scanning right down. And then we use this software to use these and then segment these datasets to convert them into 3D models, and then we can use them for animations. So, say we have a CT scan of a man, we can then go in, use the software, actually visualize his skeleton in 3D and then export this into ZBrush or something, clean it all up, cut it all up, then put it into Maya and rig it up. So, we can actually use real human data to make these things as well.

Joey Korenman:

Wow. Okay-

Emily Holden:

Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

I have a question about that.

Emily Holden:

I'm sorry if that was a lot of jargon, but I hope-

Joey Korenman:

Well, no, I mean, I-

Emily Holden:

It came across.

Joey Korenman:

It's fascinating, to be honest. What's really interesting is there's so many similarities between what you do and then, in my previous life, when I was a creative director at a studio, I was doing the same things, just it was way easier sounding, what I was doing. So it seems like there's almost a much longer pre-production phase for this kind of work. When a client comes in and maybe they've never hired a medical illustration company before, how do you manage the client so that they understand how much work it is to, say, take a CT scan's data and combine it and then clean it up, export ... I mean, it sounds like it could take a week or two just to be ready to even make your first image.

Emily Holden:

Yeah. I think there's the pre-production part and the research does take a lot of time. I think the main thing that separates, maybe, our animation pipeline from a more generalist animation studio would be that research and the fact that our work will ... If it is for, say, a big pharmaceutical company or something like that, then it will have to go through a medical, legal review. So, any content that we produce for clients who are involved in pharma or medical devices or nutritional products, they require a med legal review. It's also sometimes called an MLR review, medical, legal and regulatory review.

Joey Korenman:

Oof.

Emily Holden:

These companies regularly undergo med legal reviews to ensure that their products' claims and their promotions are medically accurate and comply with the regulatory standards, including a med legal review in our pipeline is a really cost-effective way to make sure that the productions go smoothly, to avoid any risk of potential litigation further down the line. So we could just go and say all right, we think it should look like this, and maybe we're talking to an agency who's working on behalf of the pharma company or something like that, and we'll get it to a point, we'll spend a lot of time and effort and, I guess, a lot of money getting to a certain point and then they come back and go ... It then goes to the legal team and they go, "No, you can't say that," or "No, you can't do that. No, it doesn't actually work like that. You can't show that."

Joey Korenman:

Right.

Emily Holden:

So it's kind of like going right back to the beginning, straighten the script. The script will probably have to go through quite a couple of reviews, and then the storyboard will have to go through a good medical, legal review as well. It's just one of those ... Yeah. It's one of those-

Joey Korenman:

Yeah.

Emily Holden:

Niggly parts of the process, but-

Joey Korenman:

It's the same in any commercial I've ever done and it just sounds like ... In your case, it's just more ... It sounds worse. The thing is if I-

Emily Holden:

Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

I'm trying to think of an example. Like showing the way an app works or something, we've all done these demo videos where you show-

Emily Holden:

Totally.

Joey Korenman:

How an app works or something. And a lot of times, the app doesn't exist yet and so you're guessing. And you'll spend a week animating all this stuff and then, finally, the client will actually show it to one of the UI or UX people and, "Oh, it doesn't actually do that."

Emily Holden:

Oh, no.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah.

Emily Holden:

Or it's like, "Actually, that button is actually ... Just the other side of the screen and it"-

Joey Korenman:

Right.

Emily Holden:

And you're like, "Well, that would've been nice to know a couple of weeks ago."

Joey Korenman:

Yeah.

Emily Holden:

Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

That's so funny.

Emily Holden:

Yeah. So-

Joey Korenman:

Wow.

Emily Holden:

Yeah. Yeah, it's very similar, I guess, if it's pharma and stuff like that, if it's to do with-

Joey Korenman:

I mean, the stakes are high.

Emily Holden:

Yeah, the stakes are high-

Joey Korenman:

The stakes are much higher, so.

Emily Holden:

If it's drugs and stuff like that, yeah. So that's maybe the slight difference, but I guess it all follows the same process. We start with script, storyboarding, couple of reviews, modeling, an animatic, just the regular-

Joey Korenman:

Yeah.

Emily Holden:

Process.

Joey Korenman:

Standard stuff.

Emily Holden:

Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

Love it.

Emily Holden:

Standard stuff, yeah.

Joey Korenman:

Well, this has been a really awesome conversation. So we've talked about cadavers-

Emily Holden:

Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

And we've-

Emily Holden:

Oops.

Joey Korenman:

We've talked about taxidermy and we've talked about Arnold Renderer. I mean, really, this conversation's been all over the place, but it's been-

Emily Holden:

I know, I'm sorry.

Joey Korenman:

Really ... No, no, it's been amazing. I mean, really, going into this, I assumed I would find a lot of similarities between the work you're doing and the work that I used to do and the work that most of our students are doing. And, really, it's the same thing, there's just this extra piece to it where you do need to have this medical knowledge, it sounds like. And so the last thing I wanted to ask you, because, secretly, what I was hoping was that everyone listening to this realizes oh, wow, this is a thing I didn't even really know about. I didn't know that this was another avenue that you can take your motion design skills. And I know you're saying that it's a nice sized industry, but another thing you said, Emily, is that there's not a ton of competition, which-

Emily Holden:

Oh, wait. Ooh.

Joey Korenman:

Now maybe you want to take that back, but-

Emily Holden:

I'm going to ... Yeah.

Joey Korenman:

Yeah.

Emily Holden:

If you're a generalist animator, much bigger market. It's huge.

Joey Korenman:

Sure.

Emily Holden:

Compared to ... Yeah. [inaudible 00:58:53].

Joey Korenman:

Yeah.

Emily Holden:

So it's not-

Joey Korenman:

But, I mean, this is ... For the right type of person, this just seems like such a rewarding field and just a really cool way to use these skills. So I was wondering if you had any thoughts. If someone's considering pursuing this, they're like, "This sounds really interesting. And I'm into biology and I'm into science already, maybe this combines two things I love." What type of artist is going to be successful in this field?

Emily Holden:

Yeah. I think, like you said, anyone who's interested in medicine or anatomy would love doing this job. I think it's good to have people who are lifelong learners in it and have very good analytical skills because they'll definitely succeed. It's the same with, I guess, if you're animating anything, I guess, but there's a heavier part of the research, but I find research fun. I think learning about these things are really interesting and fascinating.

ENROLL NOW!

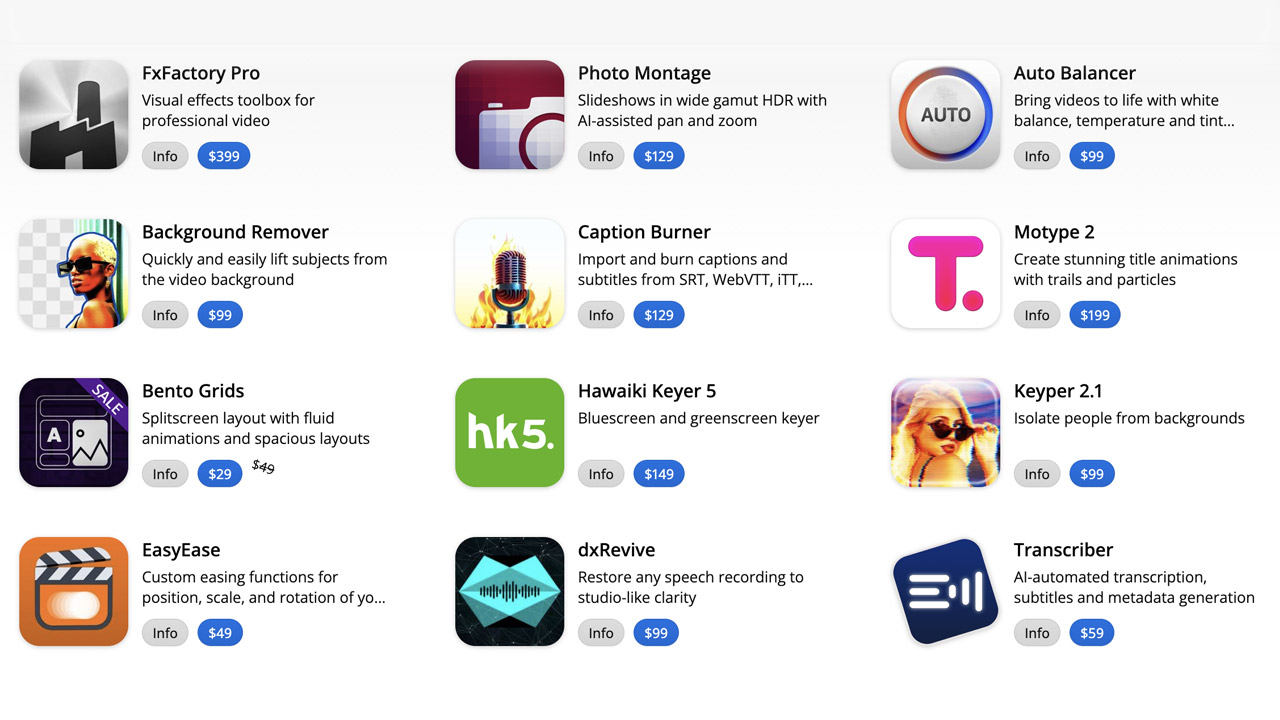

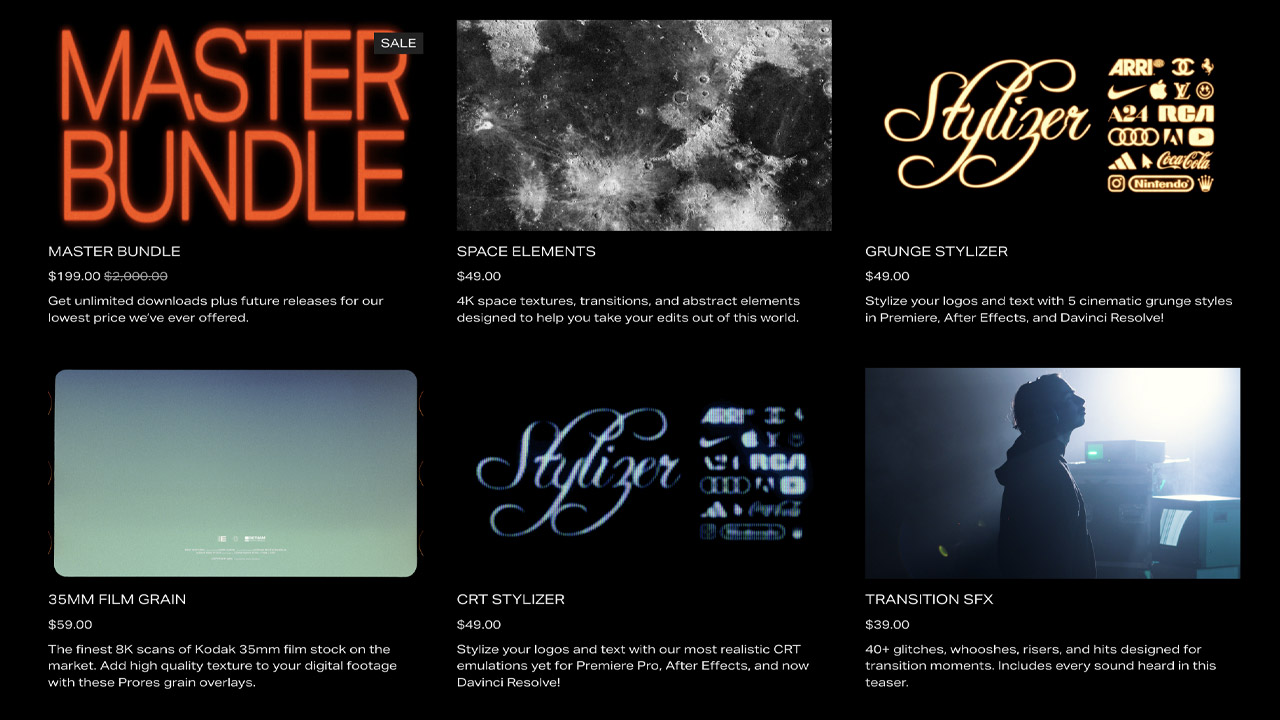

Acidbite ➔

50% off everything

ActionVFX ➔

30% off all plans and credit packs - starts 11/26

Adobe ➔

50% off all apps and plans through 11/29

aescripts ➔

25% off everything through 12/6

Affinity ➔

50% off all products

Battleaxe ➔

30% off from 11/29-12/7

Boom Library ➔

30% off Boom One, their 48,000+ file audio library

BorisFX ➔

25% off everything, 11/25-12/1

Cavalry ➔

33% off pro subscriptions (11/29 - 12/4)

FXFactory ➔

25% off with code BLACKFRIDAY until 12/3

Goodboyninja ➔

20% off everything

Happy Editing ➔

50% off with code BLACKFRIDAY

Huion ➔

Up to 50% off affordable, high-quality pen display tablets

Insydium ➔

50% off through 12/4

JangaFX ➔

30% off an indie annual license

Kitbash 3D ➔

$200 off Cargo Pro, their entire library

Knights of the Editing Table ➔

Up to 20% off Premiere Pro Extensions

Maxon ➔

25% off Maxon One, ZBrush, & Redshift - Annual Subscriptions (11/29 - 12/8)

Mode Designs ➔

Deals on premium keyboards and accessories

Motion Array ➔

10% off the Everything plan

Motion Hatch ➔

Perfect Your Pricing Toolkit - 50% off (11/29 - 12/2)

MotionVFX ➔

30% off Design/CineStudio, and PPro Resolve packs with code: BW30

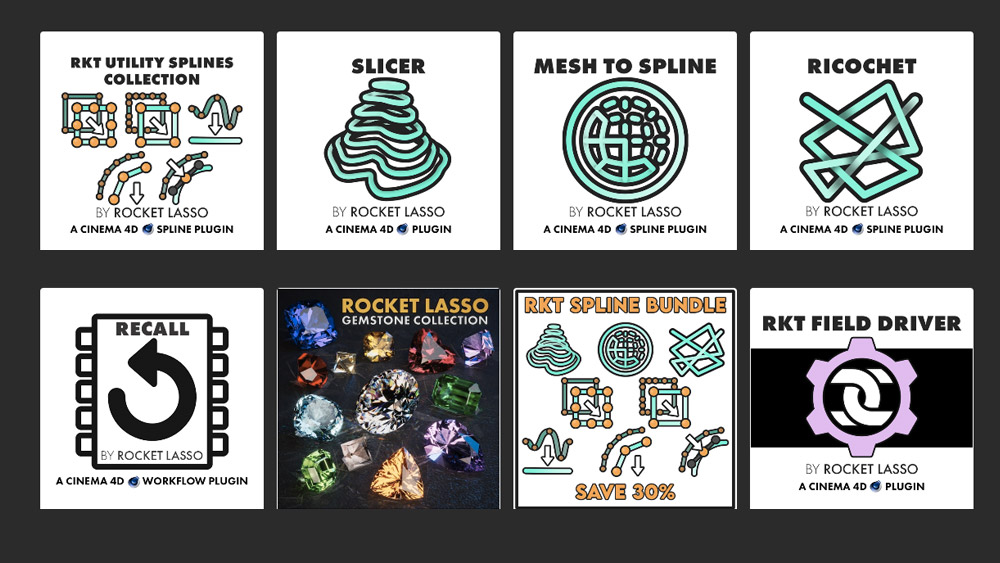

Rocket Lasso ➔

50% off all plug-ins (11/29 - 12/2)

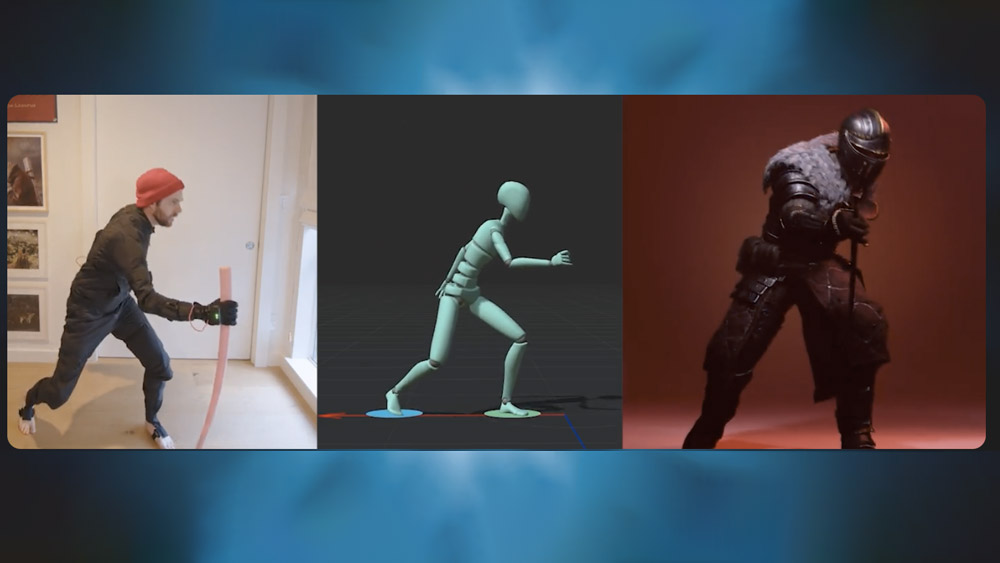

Rokoko ➔

45% off the indie creator bundle with code: RKK_SchoolOfMotion (revenue must be under $100K a year)

Shapefest ➔

80% off a Shapefest Pro annual subscription for life (11/29 - 12/2)

The Pixel Lab ➔

30% off everything

Toolfarm ➔

Various plugins and tools on sale

True Grit Texture ➔

50-70% off (starts Wednesday, runs for about a week)

Vincent Schwenk ➔

50% discount with code RENDERSALE

Wacom ➔

Up to $120 off new tablets + deals on refurbished items